Copyright is for Losers? The Turbulent World of Modern Graffiti

Last month an exhibition and auction of twenty works by the world renowned graffiti artist Banksy was held in the heart of London. The artist himself however appeared to condemn the event, which was organised without his involvement or consent, and issued a statement on his website declaring it “disgusting [that] people are allowed to go around displaying art on walls without permission”.

Whether Banksy’s protests were intended to be taken seriously or (as is perhaps more likely given their irony) humorously they bring to the fore questions of ownership and control that concern many involved in modern graffiti art. The growing trade in these works has brought some of the parties involved into conflict, with graffiti artists upset to find their pieces sold or copied without permission; locals angered by the removal of freely given art for private profit; and auction houses defending the rights of property owners to sell their graffiti covered objects without interference.

These clashes are however rarely resolved through legal actions: Banksy himself even famously declared that “copyright is for losers”. Yet with many graffiti works now worth hundreds of thousands of pounds, and the UK public increasingly accepting them as art, is it really the case that copyright has nothing to offer these creators?

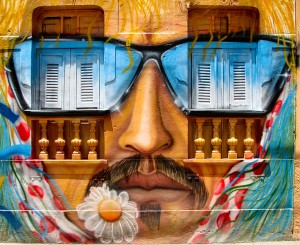

Image available under CC BY-SA 2.0 by dumbonyc

As a starting point, it certainly appears that copyright in graffiti can exist. According to the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 copyright subsists in artistic works (amongst other categories) and “a graphic work” is considered to be a type of artistic work for these purposes. Paintings are expressly included within the non-exhaustive definition of a graphic work provided in the Act and, while the term “painting” is itself is not defined at any point, it has been suggested that its interpretation in UK case law could allow for graffiti to qualify as an artistic work under this heading.

It is important to note that, for graphic works, copyright protection can exist irrespective of their artistic quality. Furthermore, even where the graffiti has been illegally created, as is often the case, it is not necessarily barred from copyright protection as the UK copyright legislation doesn’t take into account the purpose behind the work when determining whether it qualifies for protection. Both legal and illegal graffiti thus can potentially be covered.

Provided, therefore, that the individual piece of graffiti meets the statutory requirements for copyright to arise in an artistic work – which includes, most notably, a requirement that the work be “original” – it would appear that graffiti can qualify for protection. Indeed, some commentators have even suggested that graffiti ‘tags’ could be protected in this manner as long as their presentation displays enough creativity to constitute an artistic, rather than literary, work.

Copyright will automatically come into existence where the requirements are met and will, except in certain specific circumstances, initially belong to the graffiti artist who authored the work. As a result copyright can therefore be of some use to these creators, as it grants them a number of exclusive rights including, most notably, the right to prevent others copying the work without permission.

Image available under CC BY-SA 3.0 by Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

However, while copyright allows the graffiti artist to prevent others making copies it does not allow them to stop others from selling the original, physical embodiment of the art. Most graffiti is painted onto property that belongs to a third party and, as such, the resulting object remains the property of that third party. As owner, the third party is free to do whatever they wish with it; they can remove it, destroy it, or sell it on as they please.

There have been some attempts, most notably in the US, to argue that the moral rights granted under copyright could help creators in this regard. A creator’s right to prevent the derogatory treatment of their work, it has been suggested, could potentially allow creators to resist the destruction or removal of their work. Such arguments were however unsuccessful in the US and it seems unlikely that they would fare much better in the UK, especially for works which have been created illegally.

It is worth noting though that the graffiti artists would still have the moral right, if their work is protected by copyright, to be identified as the author of their works irrespective of whether they can control their sale. However, this right must be asserted in writing by the artist before it can be infringed by others. While some graffiti artists do sign their works with their name or pseudonym, fulfilling this requirement and allowing them to assert the right, many others do not. These latter artists would have to take action in order to assert their right (in one of the manners outlined in section 78 of the legislation) before others can be found to have infringed upon it.

Also, while they may not be able to block the sale, a graffiti artist may nonetheless still be entitled to claim a royalty on the net purchase price under the Artist’s Resale Right. There are some restrictions on the circumstances in which this Right applies – the sale must be for over €1000, for example, and must be exercised through a collecting society – but nonetheless the creator could potentially be entitled to up to €12,500 in royalties, depending upon the value of the sale.

Image available under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 by Jakub Redziniak

There is however a significant difficulty when it comes to taking advantage of these rights in practice. In order to take advantage of copyright a graffiti artist must identify themselves as the author of the piece. However, unless the property owner has given their permission for it, graffiti is illegal and can lead to criminal charges for its creators under a number of UK statutes. If an artist thus identifies themselves as the creator of a work in order to benefit from copyright protection, or to claim funds under the Resale Right, they open themselves up to fines or even jail time under the criminal statutes. Additionally, there would also be the further possibility of civil claims from the owners of the property that was defaced by the graffiti.

Even where graffiti is legally created artists can face a factual challenge proving their authorship of the piece. While there is a legal presumption of authorship for works containing a signature that claims to be of the artist, many graffiti works are unsigned. While their authors can often be identified through the distinctive styles used and their reputation in the local community proving this may be difficult in court.

Overall, it would appear that copyright is a mixed bag for graffiti artists. On the one hand copyright doesn’t allow artists to protect the physical embodiment of their original artistic works, and it can be challenging in some circumstances to take advantage of copyright in practice. On the other hand however, it can allow artists to control the copying of their work; can enable them to claim royalties when the original is resold; and, at the very least, can allow them to insist upon recognition as the author of their creations. Far from being just ‘for losers’ therefore copyright has the potential to be a useful tool for creators in what is increasingly becoming a valuable art form.